Educational interventions to address the challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic need to acknowledge the realities of life in the most disadvantaged communities if they are not to exacerbate existing inequalities, argues Rakhat Zholdoshalieva

The magnitude of the global health crisis, and the long-term impact it is likely to have on the economy, society and education, was unimaginable just a few weeks ago. Such crises spark understandable fear and anxiety, as we come to terms with the impact both on our physical and psychological health and on our economic, financial, environmental and social life in the months and years to come.

As someone who works in adult learning, with a focus on youth and adult literacy and people who experience multiple forms of discrimination and disadvantage, I observe that many of our evolving solutions, advice, lessons and reflections ignore the reality of life for many children, youth, adults, families, communities and regions around the world. In times of massive disruption, disorientation and anxiety at global level, it is more important than ever that we do not lose sight of those who historically have been out of sight and out of mind when it comes to policies and actions.

We are experiencing closures on an unprecedented scale, whether of borders, schools, universities or public spaces. To tackle these closures and ensure some continuity of engagement with society, education or work, our immediate preoccupation has been to enable this through a variety of short-term low- and high-tech distance and online solutions. Big data enthusiasts must be reaping the benefits of the fact that a lot more people are now learning and working online and knowingly or unknowingly sharing their information.

As an educationist, I closely follow the accumulating impact of this global crisis on education and the rapidly evolving solutions. So far, these solutions have predominantly centred on children and young people, especially those enrolled in formal education institutions, neglecting those children, youth and adults who are already disadvantaged in terms of these kinds of opportunities. Gradually, the solutions on offer have begun to reflect some of the lessons for engaging those who have been ‘left behind’ and to draw on practical lessons from first-hand, local experience.

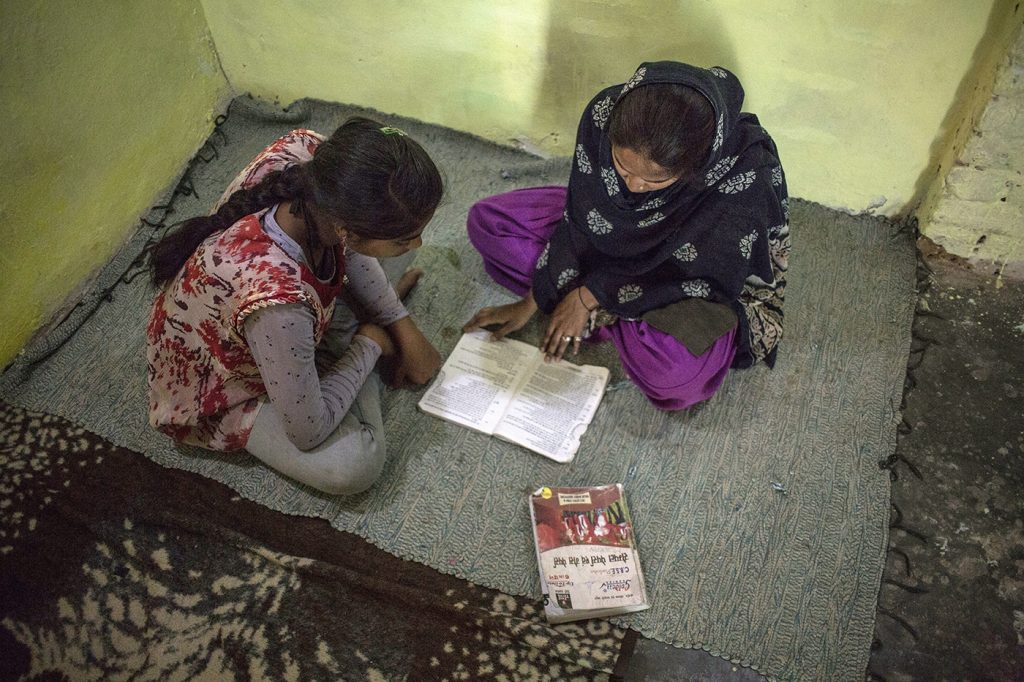

However, while this recognition is welcome, we are still some way short of recognizing the extent and entrenched nature of some of these pre-COVID-19 era issues. One such issue is the unavoidable fact that a large proportion of youth and adults are denied opportunities to acquire basic skills. Around 750 million youth and adults lack basic literacy skills. Most of them live in developing countries, and a disproportionate number are women. They are more likely to live in rural and remote regions, to speak a minority language, and to have had to leave their homes because of conflict, disaster, or in search of better livelihood. What about their access to quality learning and education? How can digital solutions for educating children and young people work for adults? How can high-, low- or no-tech solutions to educational access and quality support current and future engagement with excluded youth and adults? And how should we ensure that funding such solutions does not come at the expense of investment in adult learning programmes? It is worth remembering that youth and adult literacy is not well funded, despite the huge global scale of the challenge.

As nations focus on preventing the spread of COVID-19, hastily investing in research and vaccine development, while identifying the best ways to reduce the economic impact, this global health crisis is also teaching us longer-term, global lessons. One is that we need to recognize the deep inequalities in terms of age, gender, race, and geographic location, and how such crises disproportionately affect those who are already the most disadvantaged. Another, more positive lesson concerns the cooperation and solidarity we have seen among communities, cities, nations and institutions. This newly discovered spirit of solidarity is the key to finding solutions and ensuring a better present and future for all, not just a few of us. This should extend to ensuring quality lifelong learning for all, including those youth and adults who have been left behind, so that our collective actions include everyone.

In the post-COVID-19 era, it will be critical that we re-energize global efforts to address existing issues such as the large number of youth and adults who lack basic literacy skills. We also need to ensure that the meagre amounts currently invested in youth and adult literacy programmes are not redirected towards other initiatives that better resonate with the current preoccupations of donors, governments, planners, communities and the general public. We are experiencing this global health crisis together, our memories are fresh and collective, and we must ensure the solutions we find work for everyone.

Rakhat Zholdoshalieva is Team Leader, Policy Support and Capacity Development in Lifelong Learning, UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning

For education interventions, when it comes to Formal Education (FE) and None-Formal Education (NFE), it is very true to focus on “finding solutions that work for all” not only for one. Mostly, these two wings of one bird are treated differently by the countries. Usually, NFE is less taking into account compare to FE in terms of budget and other resources allocation, while the target group of this part is those illiterate youth and adults who have already missed many opportunities and as stated by Ms. Rakhat they are very disadvantaged group of people who live in the remote areas under poverty line and speak minority languages . If they are not focused in the crisis such as COVID 19, they will be impacted compare to everyone else.