The COVID-19 crisis has made online distance learning the new norm for many. It has also prompted stakeholders to be more creative and agile, in ways that could make open and online learning better and more inclusive, writes Jonghwi Park

COVID-19 has been with us for a little over four months now. Its impact on the world in that time has been remarkable and unprecedented – a third of the world’s population have been living under lockdown, as many as 91 per cent of school students have faced schools closures in April, and 195 million people are projected to lose their jobs.

Few areas of human life are untouched by the crisis. From techniques to prevent back pain when working from home to the challenges of home schooling, the demand for new knowledge has created an urgent need for learning, unlearning and relearning to deal with new normalcies. For those at risk of losing their jobs, reskilling or upskilling is not a choice but a necessity. Many of us face a steep learning curve in adapting to these new circumstances. This new learning, while undoubtedly challenging, is, however, critical if we are to emerge from this crisis into a better future.

National educational responses have focused on learning at school. Education authorities around the world have announced emergency plans to ensure the continuity of school learning, ranging from unprecedented full-online school reopening for the entire K-12 population, to home-based learning using low-tech solutions such as emails, TV and radio, and no-tech interventions such as delivering learning materials by post. By contrast, many adult learning courses have been suspended for various reasons, with sometimes devastating consequences for those already in need of urgent learning support, for example, refugees and migrants, unemployed people and parents in rural areas who want to support their children’s home learning.

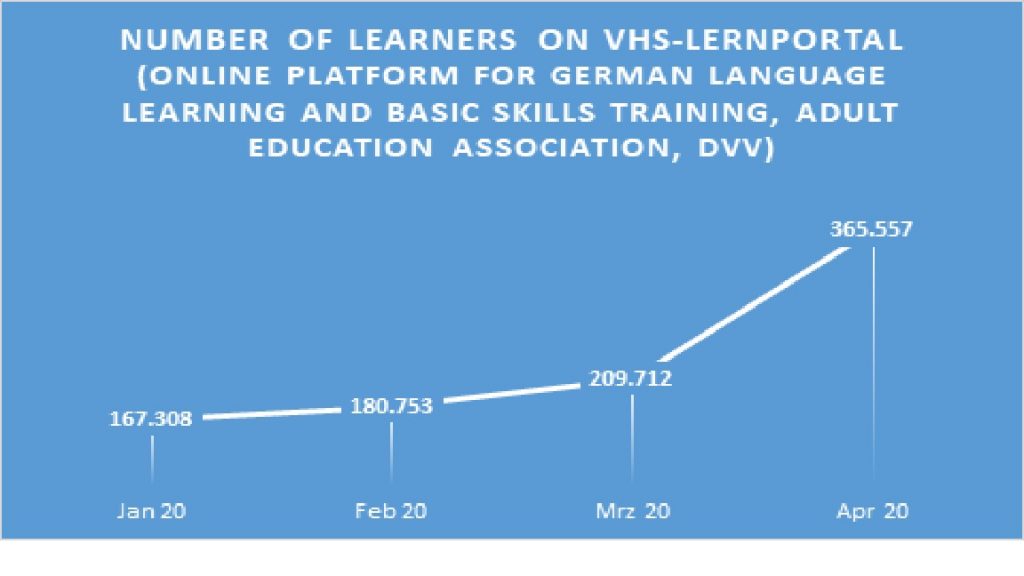

Despite the suspension of many conventional adult education programmes, there have been some positive developments in using technologies to meet emerging learning needs. Enrolment in massive open online courses (MOOCs) has been soaring and a list of 450 free Ivy League courses has gone viral. Coursera, a major MOOC provider, reported a 607 per cent increase in enrolments in March and April compared to the same period last year, with the greatest increase in public health, arts and personal development courses. In Germany, the adult learning centres operated by Deutsche Volkshochschul-Verband (DVV) experienced a drastic increase of 150,000 new learners in April after the Federal Office for Migrants and Refugees announced its support for online tutoring for integration and language programmes.

In Namwon, a city in the Republic of Korea, the lifelong learning centre has sought to ensure continuity of second-chance education by making telephone calls to each learner and guiding them to take credible online courses. And in Thailand, a development research centre called CCDKM, based in Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University, provides micro online learning on demand for marginalized groups such as ethnic minorities and rural women. In the context of the pandemic, the centre is offering a short video course for taxi drivers to enable them to communicate with foreigners who refuse to wear masks (see below).

While there have been some very positive innovations, concerns remain. According to a study, a quarter of the most viewed YouTube videos related to COVID-19, accounting for 257,804,146 views, contain misinformation. Such trends highlight the urgent need to foster critical media and digital literacy skills.

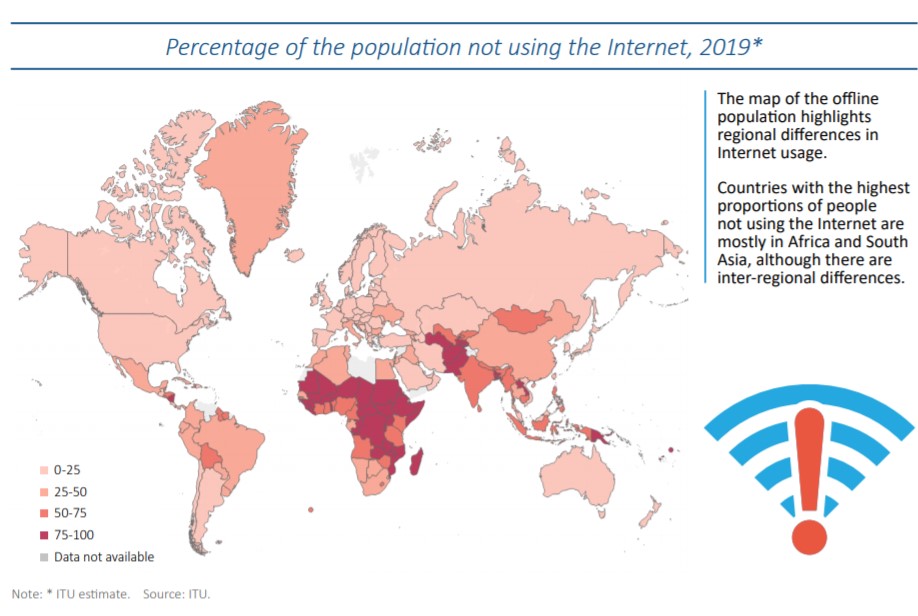

Another, more fundamental, concern is access to the internet, particularly in the Global South. All this wonderful open and free learning depends on learners having stable connectivity and devices, as well as fluency in the dominant languages of the internet. However, almost half of the world’s population did not have internet access in 2019 (see map below). Most of these offline populations reside in the least-developed countries, in which growing gender gaps in access to the internet also persist.

A third concern is that proofs or credentials recognizing acquired knowledge or skills are, in many cases, unavailable for open and online learning. Most MOOCs cease to be free when learners require credentials. For that reason, some critics argue that they are just another imperfect, over-hyped ed-tech intervention that widens the gap between rich and poor.

There is no single solution to address the pitfalls of open and online learning for adults. However, the pandemic has forced all players and stakeholders to be more creative and agile and this could potentially lead to improved and more inclusive open and online learning.

The challenges are significant. Recognition of informal learning (such as open and online learning) requires a massive reform of national qualification frameworks or professional standards. Some lifelong learning enthusiasts and blockchain engineers have taken proactive actions to get online learning recognized. With a multi-partnership programme with accredited providers and secured digital learning identity, Learning Beyond Borders set up trusted credentials for refugee camp education in Uganda and help them track and accumulate their online learning records.

Increased investing in adult learning is critical, not just for improving skills for employment and contributing to national economic growth, but also for improving community and public health and wellbeing. For this to happen, adult learning requires the support of numerous players. Above all, government commitment in orchestrating multiple players and providing an enabling environment is paramount. In Bhutan, the government launched its second ICT in Education Master Plan in 2019. The plan considers non-formal education an integral part of national education and explicitly allocates ICT infrastructure for community learning centres and ICT skill training for NFE educators. It says the investment will ‘enable NFE learners to access the ICT‑mediated public services such as government-to-citizens (G2C) services to ease their life and use digital resources responsibly’.

It is important too that we continue to revisit and adapt low-tech solutions. The Education Development Centre, for example, has set out how to reuse and revamp the old video/audio materials. UNESCO’s list of distance learning solutions includes offline platforms mimicking online OER (open educational resources) repositories such as Kolibri. UNHCR’s excellent guidelines for connected learning for refugees under COVID-19 give hope of extending the benefits of national education to this vulnerable group. We also need to ensure that appropriate mentoring and counselling are in place, especially for adults with low literacy skills and in vulnerable situations.

No one knows how long the pandemic will last or to what extent it will change our lives and the ways in which we manage our education and learning. Its consequences are deep and unpredictable and challenge us to reflect not only on our own behaviour but also on how we organize our societies. As Yuval Harari said, the pandemic will pass but the world that emerges form it will be different in many ways. In such circumstances, the case for lifelong learning is stronger than ever.

Jonghwi Park is a Programme Specialist, UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning

This is very commendable. Its amazing to see the impact of digital learning on education especially in the developing world.